Premier

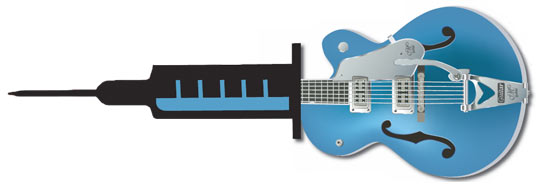

Guitar, Nov '07 - Anabolic

Rock

by Jim

McGorman

In

this age of technology, we can do more with less. But as technology

capable of turning non-musicians into stars becomes a bigger part of

the recording process, how will we know what is “real” or “fake”?

On the evening of August 7, 2007

Barry Bonds did what was considered a

Herculean feat in sport, surpassing Hank Aaron for the most career home

runs in major league baseball (at the time, 756). As the ball sailed

all 435 feet out of AT&T Park, I paused to consider the conflicted

feelings I had about an amazing sport and this recent milestone. It’s

obvious to any fan of the game that Barry Bonds is an amazing baseball

player, but his alleged steroid use unfortunately calls into question

the legitamacy of his achievement. FOX’s Tim McCarver said of the

event, “Only time will tell if baseball’s steroid era will result in a

number of asterisks within the record book, but there are already

mental asterisks in the minds of fans. It’s a shame that, after Bonds

breaks the record, the conversation will go, ‘Barry is the all-time

home run hitter, but…’ This record deserves more than that. With Henry

Aaron, there were no buts.”

But I digress, this isn’t an article about baseball or steroids –

although I think there are some serious parallels between the two.

As a working musician, much like any athlete, I am always looking for

ways to improve my abilities, whether it is through more practice or by

utilizing the latest technology available. When it comes to your

passion, I can certainly sympathize with anyone who is trying to gain

an edge in what they do.

And while I embrace the merging of technology with music, on the other

hand (much like a vast majority of baseball fans), I am a

traditionalist. I starting learning music at a time when computers were

not heavily used, either in recording or instruction. I took piano

lessons when I was very young, and I taught myself how to play guitar

by watching others and looking at books. After high school, I attended

Berklee College of Music where I really explored the history of music.

I honed my craft. I learned what makes it what it is. And now I have

been playing music professionally for over ten years now – I have been

in a position to witness the explosive expansion of technology and how

it has become a mainstay in today’s music business.

The Tech Boom

No matter where you stand on tradition, it can’t be denied

that many of

the things that have come out of this technological boom have improved

the quality of music and made musicians’ lives easier. A few of my

favorites are the now ubiquitous iPod; Pro Tools and the wide variety

of available plug-ins, making recording faster, easier and limitless;

new keyboard technology and the ability to manipulate sounds with

almost limitless variation and little sweat; virtual instruments,

allowing you to have an orchestra at your fingertips; and

non-destructive editing of sound files. All of these product

innovations are amazing, inspiring and aid in our abilities to create

and enjoy music.

Of course, as with any great innovation, there is the inevitable

downside. All of these products are insanely powerful, capable of

creating amazing musical miracles. Perhaps it was said best by Peter

Parker’s Uncle Ben in the comic Amazing Fantasy #15, “With great power,

comes great responsibility.”

The manufacturers of these technologies are constantly and

simultaneously loading them with more features and making them easier

to use. Now, a person who takes the time to learn and manipulate these

products can create something that sounds unbelievable with little or

no human input – in a historically unique moment, it is now possible to

make a record or create music without the playing of any instrument!

With the help of modern technology, you could take an average voice off

the street and make it sound like Pavarotti. If you’re honest with

yourself, do you really believe that Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan can

sing?

That being said, there is no doubt that technology can be

inspirational. Pete Townsend’s visionary approach to sound gave us

seminal tracks like “Baba O’Reilly” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Quincy Jones blended cutting edge technology and live musicians to

create Off the Wall and Thriller. There are many producers and

musicians doing innovative work in today’s music, such as Dr. Dre and

Timabland.

But the question inevitably becomes, where does the line between what

is natural and what is fake get drawn? Is there a point where asterisks

should be placed next to album tracks, next to artist names?

There is definitely a talent to working with Pro Tools and the myriad

related products. Like graphics programs such as Adobe Photoshop, it

takes real skill to coax the potential from these applications. The

biggest qualm I have, along with many musical “traditionalists”, lies

with a new generation of musicians – and certainly not all of them –

who are using technology to compensate for a lack of talent and

originality. Tuning programs like Antares Auto Tune and Melodyne can

create a vocal performance that would never have been possible from the

singer’s own voice (more about these later).

From a

rhythmic perspective, if you were to “grid” a classic Rolling

Stones song in Pro Tools or Logic, you would discover the time is

shifting all over the place. The click track might go out the window,

but the song would still groove.

There are also several programs designed to place music in the exact

right time by using a grid. Quantizing programs like Beat Detective

allow the musician (or non-musician) to play “out of time” and

magically have it sound in time. Eric Robinson, a producer, engineer

and artist in Los Angeles summed it up, saying, “Technology enables

processing that used to be impossible or incredibly time-consuming to

be done at light speed and easily repeated. This is where many people

lose sight of what they are working on and rely on technology to fix

what they either can’t do or don’t want to spend the time to make

right.”

Correcting the Pitch

Over the last ten years, audio engineers have been

perfecting a

technique called “pitch correction or tuning,” in which they take

someone’s recorded lead vocal and “put it in tune” with the use of

various computer programs that allow the note to be altered into

perfect tune. As with anything else, there are good and bad sides to

this. The obvious upside is that if the singer sings flat or sharp, it

can be fixed after the fact. It is a relatively quick procedure and can

save valuable studio time if a singer has difficulty hitting the right

notes – an engineer can do this in a home studio at little or no cost

if they have the right programs. And let’s face it; it also sounds

good. No matter how much of a traditionalist you might be, no one wants

to hear someone singing out of tune.

As the technology has become more widespread, especially in the past

few years, our ears have become accustomed to the sound of “pitch

correction.” The downside of this is that when you hear an artist

singing live, who was “pitched” severely on their record, you will hear

a significant difference. Lead and background vocals are almost always

pitched, creating a homogenized syrupy sound. In addition, pitching a

great singer can take away a lot of the character of the performance.

The slightly flat notes, awkward vibrato and odd phrasing are some of

the things we love most about our favorite pre-Pro Tools records.

If Led Zeppelin were set to record a new album in 2007, it would most

likely sound nothing like the original recordings that we love so much.

The undeniable vibe of the four guys playing together would likely be

tainted with the modern attitude of fixing everything and making it

“perfect.” From a rhythmic perspective, if you were to “grid” (put the

song on a quantized grid that places the audio into blocks, so you can

determine whether something is in time or not) a classic Rolling Stones

song in Pro Tools or Logic, you would discover the time is shifting all

over the place. The click track might go out the window, but the song

would still groove. The mojo is still there. Mick Jagger’s voice is raw

and untainted.

Recording to tape preserved the artists’ original take for perpetuity.

Of course, they would do multiple takes and plucky engineers had some

editing tricks (splicing, doubling, etc.), but there were no digital

enhancements that helped Mick Jagger sing in key, even if he couldn’t.

Back then, you had to perform to make the big money. Real performers

like Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett grabbed the mic (sometimes doing it

without one) and just sang. They were entertainers, and they were able

to develop their abilities, but it all started with talent. There were

no computers involved.

I spoke with my friend and record producer, Marshall Altman from his

recording studio in Burbank, California and asked him if he could weigh

in on this topic. Here’s what he had to say:

“As users and creators of technology, we just might be contributing to

the death of rock n’ roll, yes. But as Bruce Springsteen said,

‘Everything dies, baby. That’s a fact. But maybe everything that dies

someday comes back. Put your make up on, fix your hair up pretty, meet

me tonight in Atlantic City.’ Do you think he’d have written that on an

MBox, had the technology been available? I’d like to think he would

have.

“So yes, technology is contributing to the death of music in general,

not just rock n’ roll, and I say let it die. Let it all die, so it can

grow back in to something scarred and beautiful, tragic and noisy,

brave, bold, stupid, smart, happy, sad, life-changing and everlasting.

“Let the major labels die a slow, painful death, and let bold new

record companies rise like roses growing in the cracked sidewalks of

popular culture. Let every band with enough money buy the gear they

want, make a record with too much compression and not enough heart. Let

every singer-songwriter who suffers from having read too much and not

having lived enough make a record, too.

“Let them all come – put them all up on MySpace. The end is near! And I

can’t wait for the end, so we can all start listening again. It’s not

pretty out there; there’s too much good music and not enough great

music. With the advent of the affordable DAW, every kid with a dream

and a little money can make a good-sounding record, with some good

songs, and some really good artwork. Good is within everyone’s reach,

and technology has afforded us the easy opportunity to be good, but

good is not great.

“If something is great, the technology used in creating it doesn’t

matter. If there is blame to be cast, it shouldn’t fall on the

technology that has given us the opportunity to be creative. The blame

falls on our shoulders. We listen, we buy, we rip, we steal. We settle.

And out of the destruction of it all will come something wonderful. I

can’t wait to hear what it is.”

Though I started writing this article months ago, I recently caught

MTV’s latest perverse act: the performance by Britney Spears at the

Video Music Awards. Ignoring her lethargic, robotic performance and the

media’s unhealthy obsession with her weight, the debate centered on her

poor lip-syncing skills. As I realized people weren’t upset by the fact

that she was not singing, but instead by the fact that her lip-syncing

wasn’t up to snuff, I realized that the debate of tradition versus tech

isn’t going away anytime soon. It basically seemed that we as popular

music consumers are saying, “We are willing to buy something totally

fake, we just don’t want you to tell us that it’s fake.”

At this point in our musical and cultural evolution, we have weapons of

mass deception and it would seem that no one cares. If Barry Bonds

juiced, is it still a record? If you can’t sing on pitch, are you a

singer? If our kids cheat in school, will we start putting asterisks

next to the As? If video truly killed the radio star, then Pro Tools

has put real musicians in a coma.

Jim

McGorman is a professional musician who has worked with a diverse

group of artists (Avril Lavigne, Michelle Branch, Cher, Poison, Paul

Stanley, New Radicals, etc.). He is a singer, songwriter, producer and

multi-instrumentalist (piano, guitar/bass). In addition to music, Jim

currently contributes to a number of magazines and on line

publications.

Link to the article

|